Product market fit is one of the most talked about but least understood aspects of early stage startup growth. It’s a favorite subject among angel investors and founders alike and or good reason – it often points to the first major inflection point of a startup – the potential to scale.

In my experience working with now hundreds of startups, I’ve often been surprised at how little this concept is understood. So I set out to try to define what product market fit is, as well as outline a couple resources for measuring whether or not you have it.

In researching a definition, I came across this Wikipedia article which says that there are 2 popular ways to measure PM fit:

1. The 40% rule

According to Wikipedia, you have PM fit if “at least 40% percent of surveyed customers indicate that they would be ‘very disappointed’ if they no longer have access to a particular product or service. Alternatively, it could be measured by having at least 40% of surveyed customers considering the product or service as “must have”.

2. Analytics metrics

The other way Wikipedia describes product market fit is if “There are five metrics any online business can measure to empirically verify if they achieved Product / Market fit. They are 1. Bounce Rate, 2. Time on Site, 3. Pages per Visit, 4. Returning Visitors, 5. Customer Lifetime Value” and “If these 5 metrics are above average and your 40% rule is met, you’ll know you have a Product / Market Fit company.”

Superhuman’s PM fit engine

Many of us have been inspired by Superhuman’s approach to growth (detailed question based onboarding, makes it feel super personalized – followed by a mandatory call with a team member of Superhuman for onboarding), and some of us have seen the founder Rahul Vohra’s product market fit engine. This too uses a similar 40% format to help you understand if you have product market fit. This is probably my current favorite in terms of simple ways to determine PM fit.

Challenges with these models

While I believe the 40% rule is ok to use as a benchmark for your startup, how do you quantify if the 5 metrics listed above in the Wikipedia example are “above average” or not? And what happens if you either don’t have enough volume to get statistical significance with your survey or even enough volume to get directional signal that you have it?

What happens if you happen to get replies back from your early adopters, and not an objective swatch of users? And what if 50% of folks say they can’t live without it, but your wondering how you’ll ever pay the bills because when you raise prices people churn?

This got me thinking about ways early stage startups can objectively measure whether or not they have product market fit without needing to rely on survey’s alone.

How I view when we have product market fit

I tend to start to define product market fit by looking at how market ready the product is. To do this, it’s a measure of 1) revenue against payback period and 2) % of users who are finding strong value in your product and 3) you have the ability to find many more customers matching the profile of customers who fit within 1 &2.

Let’s break it down.

Revenue against payback period

This is likely the most important metric for a startup that hasn’t raised a lot of capital yet. Are you able to bring users in at a rate that supports the business? Or are you bringing in users that churn out before you break even? If you continue to bring in customers whom you lose money from, you are guaranteed to be pulling money out of your bank account. Your startup survival is simply a measure of time against money in this case.

Luckily, finding revenue against payback is pretty simple. You’ll use your retention proxy metrics to measure this (more on this topic coming soon), but if your customer acquisition cost CAC is low and churn high, that’s not viable in most situations. Alternatively, if your CAC is high and churn low, you may be OK. But there are endless ways this can play out. We’ll look at some charts below.

Growing % of users who find value in your product

Product market fit also can be measured by the % of users who find value in your product over a period of time. I call this the “proxy retention metric” or – more simply the “value” that is experienced by a customer. This is highly dependent on your business.

In the case of my growth programs for example, the value is based on the % of students who get through the entire course and apply the findings to their day to day job as a growth, marketing, or product leader.

Put simply – are your users sticking around and has your churn leveled off over time? Are users using the product in a way that they are receiving value, and are they sticking around, coming back, and telling other people about your product?

Proxy metrics aren’t normally revenue based metrics – but strong and growing revenue comes from strong proxy metrics.

You might have the most amazing product out there, but if you can’t find and retain customers, you don’t have a business. And the first step to finding retained customers is finding customers who experience value from your product and who support your proxy metricx.

Many, many highly funded startups have fallen into this trip – too high CAC, too low product value or retention, too much product complexity – leading to startup death.

Here are some examples of areas where customers may find value in different products, which is usually a signal of product market fit. These are their “proxy metrics:”

Growth University (my startup) – % of users who take my course and use the materials in their job starting in week 1 or 2

Netflix – % of users who consume more than 20 hours of content per month are likely to stick around

Amazon – # of purchases per prime member per month – if a user buys monthly they probably keep their prime membership

Costco – # visits in a year, if it’s >6 then it’s a habit and they probably won’t churn

Slack – how many messages a user reads or sends within a slack community per month

GrowthMentor – % of mentees who get matched with a mentor every time they look for help

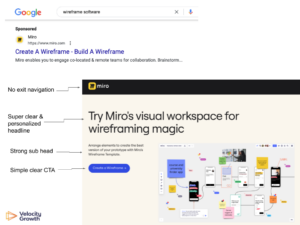

Miro – % of users who create 3 boards and hit their paywall (and then pay)

Your best friend’s substack newsletter – probably open rate and list growth by week

Why does it matter if you have product market fit?

Why all the fuss and focus on PM fit? It’s simple! Once you hit PM fit, you generally can:

- Scale your company

- Be comfortable spending $ on growth

- Have confidence in your financial modeling

- Have confidence in your retention models

How do you know when you really have it?

Look at your proxy metric activation and retention curves

I dive really deep into Activation and Retention in my Mastering Growth program. Become a Growth University member for only $1 and learn how to identify your End Point Activation goal as well as run cohort based retention modelling.

For these examples I’m using an example company and fake data so it all looks great. That being said – check out the graph below.

This is the January cohort and it measures the % of users doing the core activation metric needed for good retention. Notice how users fall off of doing the core action quickly and the curve never flattens – users just go away. This is a sign of poor retention.

If you are Netflix this will be % of users who consume >20 hours of content per month. If are me running my growth courses, it’s the % of users who tell me they apply their learnings for their startup, ask me questions, promote the course, or sign up for a 2nd or 3rd course. These are all proxy metrics for my retention.

Now look at the February cohort below. We’re doing slightly better getting users to do the actions we need them to take, but still have a sharp slope downward that never flattens.

This too is poor retention – this company hasn’t yet found a way to keep users sticking around, and unless they have a business model that supports this, it’s likely they are in trouble.

Notice the above line falls off and the % of users activated after a few months drops down to 50% then below 25%.

Now look at the March cohort. The curve flattens somewhere around month 5 or 6, then doesn’t really drop much after that. This means that the core action continues as time goes on. This is a sign of product market fit!

Notice that the line flattens. It’s not perfect – many folks do fall off, but this is perfectly normal. You know you have a sense of product market fit when these charts look better over time. It means more people as a percentage who use your product are experiencing true value, and they stick around as a result.

How do we compare against other startups?

It’s really hard to get any sense of industry benchmarks, though luckily we do have some folks publishing data here – like the amazing work by Lenny Rachitsky and Casey Winters and when we do see these benchmarks, their definitions they don’t really dive into more nuanced metrics like bounce rate, time on site, etc. I’d also argue that those core metrics above don’t actually matter all that much when objectively measuring your business and when trying to decide when to scale.

What do you do if you don’t have product market fit?

Keep trying! You need to find better target customers via better marketing, get those customers to experience core product value by having a better product, and keep them sticking around.

Considerations

There are a few key points around PM fit you should consider:

- Proxy metrics should support your long term retention

- Plot your proxy metrics over time for cohorts of users to see when the curve flattens.

- If it does so within 6-12 months, you likely have PM fit, and have a solid retention metric

Hope this was helpful! Ping me on Twitter if you have questions! Or, check out our growth programs here.

Jen is an award winning paid acquisition specialist with an honours masters degree in Digital Marketing Strategies. She is the founder of Co-founder & CMO at Velocity Growth. Jen has extensive experience working with start-ups, marketing teams and founders on their paid acquisition both in an agency and in-house capacity. She has helped companies across Ireland, UK and USA leverage phenomenal growth both nationally and internationally through paid acquisition channels.